I want to like Jesus because the grown-ups in my life told me He is good, and they were right.

I want to be innocently happy that God is good.

I want to go back to painting “JESUS FREAK” in huge letters on a baggy cotton T-shirt, soaking up Sabbath School lessons with gusto, back to the credibility God had when I was 14.

Simple Jesus—does He still exist? Or can He at least be mysteriously complex and Kindergarten-simple at the same time?

Is there a reality—no-strings-attached—in which Jesus just loves me and knows my name?

A few weeks ago I attended a spiritual retreat at Camp MiVoden, as a sponsor for the girls in the 7th/8th-grade class. During the worship services I remembered something, a feeling of belonging and certainty from my past. I knew some of the songs the praise band led, and I sang with my arms raised. No one expected anything—hardly anyone knew me—and the featured speaker said simple and good things, about who I am and who God is, and I cried, and I remembered a time when I belonged wholly, and sermons weren’t pocked with ideas that distract me from goodness and wholeness.

I want a plain friendship, one I don’t have to defend or explain, one in which I don’t need Jesus to make me look good, and Jesus doesn’t need me to make Him look good; Jesus with a reputation as simple as Mary who had a little lamb, not the notoriety of an activist.

I don’t need answers for all the questions and discrepancies. I’m looking for that place where they are absent, where I don’t have to explain why I don’t believe in a punitive gospel, or why I’m part of a faith tradition (Christianity) that has inspired violence for thousands of years. I don’t want to explain why I use feminine pronouns for God, or why I say Adventism is my community but not my religion. I don’t want anyone to raise their eyebrows at me, nor me at them. I want to be in love—inside love. I want to feel safe because I am safe.

Maybe what I really want to know is this: does a simple Jesus exist for adults too? Does He go for coffee with millennials—with me? Does He wear jeans and send 132 text messages every day? Does He understand carpools and playdates and a family calendar on the kitchen wall and how all the spoons are dirty if I miss one day running the dishwasher? Does He peruse my TBR shelf and ask me about my writing? Does He know I’m still a little girl inside, intimidated by the disciples who turn me away because I am small and simple?

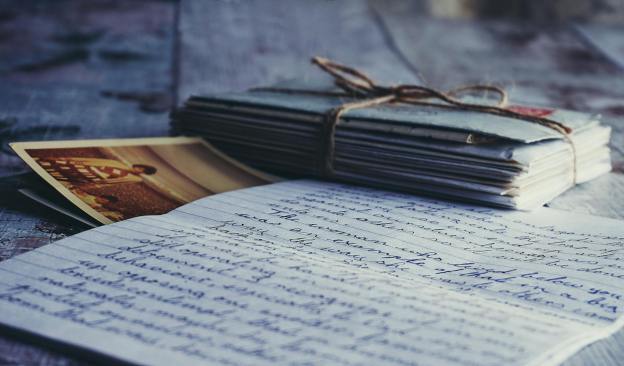

Is Jesus here now, and does He remember me? Does He look through my photo albums and murmur memories? Has He been here for it all? Can we laugh together about singing “Sinnerman” and “We Are Soldiers”—the laugh of a shared memory—those lyrics humorous like the frizzy perms of the 80’s?* Is He still the cleft in the rock, the hiding place, the blessed assurance the hymns offered?

What if we’ve shared a life more than a belief system, and our love is built on mutual adventure and admiration?

Maybe He has never needed me to pull Him apart and stitch Him back together, to understand how He is a triune being, or even to put our companionship into words. Perhaps I was mistaken in thinking that farther, bigger, and deeper are better.

Jesus is here. In the essentials He hasn’t changed a bit. He’s still the great guy I knew in primary Sabbath School; the one who stood with me in the church baptistry, invisible yet deliciously simple; the father I wrote to in a dozen journals full of prayers; the soil from which I grow. Most of all, He’s still my friend.

*I sang these songs countless times. Although the lyrics of “Sinnerman” I sang were not as heinous as what I just found by googling it, I think it’s safe to say it’s inappropriate to mock sinners running from God (and what even is a “sinner”? Aren’t we all?). And don’t even get me started on “We Are Soldiers” and “I’m in the Lord’s Army.” Who decided it was a good idea for seven-year-olds to sing about blood-stained banners and artillery? So yes, I think Jesus and I can have a good laugh about it.