It’s a few minutes before 10 AM on July 3 when I pull up in front of a quiet, fenced, red-brick home in downtown Walla Walla. The smell of warm brownies has kept me company across town, and I lift the shallow box containing towel-wrapped goodies and an assortment of papers from the passenger seat. Karen Carmen, founder of Hope Street, meets me at the front door and invites me inside with her usual friendliness and practicality.

I don’t realize it yet, but today marks exactly one year since I began my inquiry into trauma-informed writing groups. This will be my first time leading a group, and I focus my attention on setting out snacks and organizing papers. I have one hour with the five women seated around the living room, where small talk centers on a dead-mouse smell that mysteriously snuck into the house that morning. No one can tell quite where it’s coming from.

Alicia, who works here at Hope Street, passes out notebooks and pens. Then we begin with a writing prompt that will serve as personal introductions. “Finish these three sentences,” I instruct, “and then we’ll go around the circle and read what we’ve written. First sentence: I am… Second sentence: Once I bought… Third sentence: I wish…”

After a minute or two, the sounds of writing stop and we take turns reading our answers. “Once I bought…” sentences bring a few chuckles, and “I wish…” statements are trailed by affirming mmm’s and hmmm’s. Then I introduce the writing prompt that will take most of our time—a reflection on a moment with someone important to us. I set a timer on my phone for 15 minutes.

When there are two minutes left, I invite everyone to bring their writing to a conclusion, and hastily do the same with mine. I unwrap the brownies and we’re drawn in by the smell. We hold the sugary chocolate squares—and healthy apple slices—on napkins, and fall into conversation.

After our break, it’s time to read aloud what we’ve written. The women urge me to read first, so I do—I wrote about my grandma, and how she looked sitting on the back-porch swing at her home in Texas. Alicia reads next, and most of the women read aloud. They live here together, so they know each other. I am the stranger in the room and I’m honored by their trust.

We give each other feedback as I have instructed: positive comments on what you like, what stays with you, what you remember. I am surprised and delighted by the quality of writing. Each writer has used wonderfully descriptive words, and—even better—conveyed emotion. I am also surprised that we finish reading aloud and commenting on each other’s writing a few minutes before 11:00, which feels like a stroke of luck rather than a credit to my time management (running late is my cardio).

Already I like these women, and I’m thrilled when they compliment my writing and leadership and respond positively to my offer to come again. I plop my stuff back in the box, and Alicia walks me to the front door. I didn’t expect this to be so smooth, so fun, so… easy. Energized and feeling slightly inflated, I drive home, high on the joy of connection, the excitement of future possibilities, and the smell of brownies, which lingers in the warm car.

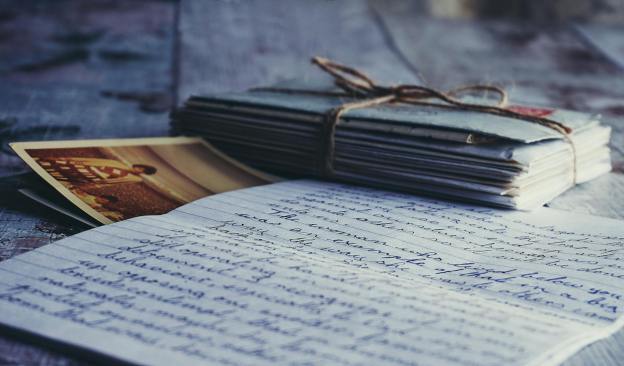

Eight hours later, I arrive at a tall brick building on the other side of downtown Walla Walla. Powerhouse Theatre is hosting a Red Badge Project reading—nearly three hours of veterans reading aloud their stories of war and life and healing. As I drove here, it dawned on me that one year ago today I attended this same event. It’s what first inspired me to spread the healing power of trauma-informed writing. I feel a moment of completeness as I settle into a seat near the front of the theater. I have returned to the place where my dream began. One small circle is complete.

I imagine that coming years will add circle upon circle, ripples of words and connection and healing. In the meantime, I continue to open my schedule, my brain, my emotions to a wider understanding of what trauma-informed means, a broader experience in writing, and a growing network of personal connections. In addition to leading the group at Hope Street and attending the Red Badge Project event, favorite moments of learning and connection in July include:

- Attending a Trauma-Informed Community of Practice meeting, hosted by Becky Turner

- Chatting with Matt Lopez at FVC Gallery, and enjoying the art displays and exquisite coffee

- Talking to my aunt Pam on the phone about writing, healing, kids, and all the things

- Participating in Janelle Hardy’s five-day, online “Stories From the Body Writing Challenge”

- Attending ITIC’s “Unlocking Human Connection: The Power of Person-Centered Thinking,” training event with Robert Peaden

- Visiting with Mindy Salyers of Counseltation about the possibility of a writing group with some of her clients (she is a therapist for elementary schools and high schools)

- Meeting Warren Etheredge after the Red Badge Project reading. Warren emceed the program both last year and this year. He is a founding faculty member and writing coach for Red Badge.

Life may not be a box of chocolates, but whatever it serves up deserves to be written down, perhaps in the safety of a living room, around a plate of brownies.

One of the women at Hope Street used the words “laughter” and “loneliness” together in her writing—a pleasant alliteration, but an unlikely pairing. I noted the way it stood out to me, paused me. And that evening at Powerhouse Theatre, as a slightly-bent older man read from the podium, the very same words came out of his mouth, one after the other: laughter and loneliness. These two words carry human experience, the feeling in our spirit of connection or estrangement, belonging or realizing we are untethered. This is why I want to write with people—so we can notice our laughter and loneliness, we can read it—speak it—aloud, we can know we are not alone.

Today’s blog post is also the most recent journal entry on my Writing Groups page. Scroll down the page to read more about what got me into this quest to form trauma-informed writing groups.